The Amen Break

The Seven-Second Heartbeat of Modern Music, Built on a Foundation of Injustice

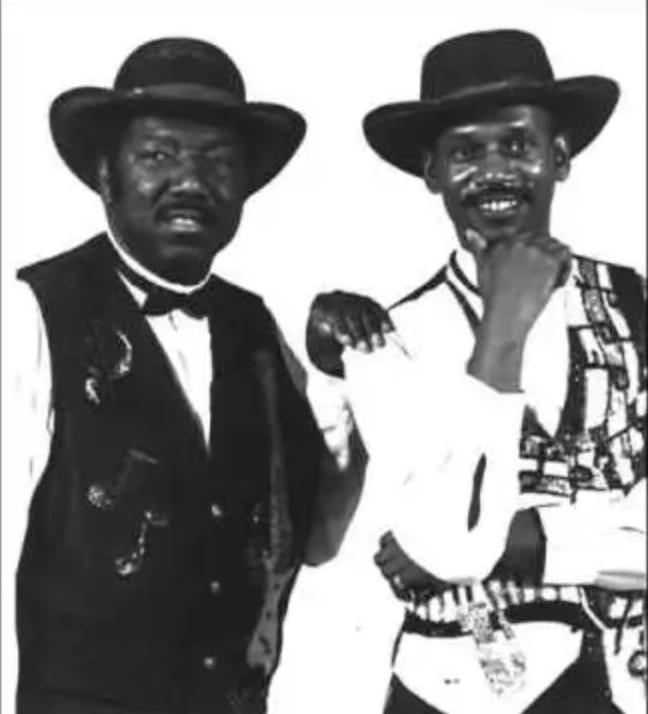

In the history of modern music, few sounds are as foundational, yet as anonymously sourced, as the The Amen Break. This seven-second drum solo, performed by Gregory Coleman in the 1969 B-side “Amen, Brother” by the soul band The Winstons, has become the undisputed heartbeat of hip-hop, drum and bass, and jungle. Its frantic, syncopated rhythm is a direct link between the Black church and the digital revolution, a testament to immense creativity. Yet, its story is also a perfect and painful allegory for how Black artistic genius has been systematically ripped off, copied, and monetized for the benefit of others while its original creators were left in obscurity and poverty.Amen

The journey of the Amen Break from an obscure funk record to a cultural cornerstone is a tale of technological opportunity meeting legal neglect. In the 1980s, as hip-hop producers scavenged record crates for unique sounds, the break was plucked from obscurity on compilation albums like Ultimate Breaks and Beats—records specifically curated for DJs to find samples. This period was the “wild west” of sampling; the legal framework had not caught up with the technology, and a “borrow now, ask later” mentality prevailed.

This allowed the Amen Break to be freely used in seminal tracks that would fuel a cultural movement without any credit or compensation flowing back to its source. Salt-N-Pepa’s 1986 track “I Desire” is one of the earliest and most influential hip-hop records to feature the break, helping to establish its utility on the East Coast. Soon after, the break became an essential tool of West Coast hip-hop, most famously opening N.W.A’s incendiary 1988 anthem “Straight Outta Compton.” That same year, it powered Rob Base & DJ E-Z Rock’s dancefloor hit “Keep It Going Now,” showing its versatility and driving force. These foundational uses locked the Amen Break into the DNA of hip-hop for a generation of producers to come.

The true injustice, however, lies in the starkly different fates of the creators versus the borrowers. The drummer, Gregory Coleman, the man whose hands created this iconic rhythm, died homeless and destitute in 2006, reportedly never knowing the global impact of his work. Richard L. Spencer, the bandleader and copyright holder for The Winstons, was completely unaware that the break had been sampled thousands of times until the mid-1990s. By then, a cruel legal technicality had sealed his fate: the statute of limitations for copyright infringement had expired for most of the early, crucial uses. The very system designed to protect creators was used to lock them out. Meanwhile, the break was being copied, repackaged, and sold by third-party companies who brazenly claimed their own copyright on the loop, a final layer of insult to the original artists.

This was not a simple case of oversight; it was a systemic failure rooted in the racialized political economy of the music industry. For generations, Black musical innovation—from blues and jazz to soul and funk—has been treated as a communal resource, a wellspring for the mainstream to draw from without proper attribution or payment. Scholars have noted that for many Black artists, their work was effectively treated as being “in the public domain.” The Amen Break is the digital-age embodiment of this tradition. The creativity was celebrated and endlessly replicated, but the creator was rendered invisible. The financial rewards were captured not by the originators, but by a downstream ecosystem of artists, producers, and, most significantly, their record labels—entities like Straight Outta Compton, Profile Records (Rob Base), and Next Plateau (Salt-N-Pepa), which generated millions from hits built on the break’s backbone.

The legacy of the Amen Break is thus a double-edged sword. On one hand, it stands as a monument to transformative creativity, a raw material that fueled entire genres and demonstrated the power of sampling as a modern art form. On the other, it is a ghost haunting the music industry, a stark reminder of the individuals whose labor was erased. The story of Gregory Coleman and The Winstons forces us to confront an uncomfortable truth: that much of the music we celebrate, from the pioneering anthems of Salt-N-Pepa to the genre-defining tracks of N.W.A, is built on a foundation of uncredited and uncompensated Black genius. Recognizing the Amen Break is not just about acknowledging a sound; it is about finally putting a name to the artist and demanding that the ledger of cultural contribution be balanced, even if far too late.

Never new that song had so many samples

Keep telling the truth of the forgotten pioneers.